On June 26, 1804, the Corps of Discovery, led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, arrived in the area that would later become Kansas City. The party was commissioned by the United States government to explore lands in and west of the newly acquired Louisiana Territory, from present-day St. Louis to Oregon. As they passed through what is now the Kansas City area, Lewis and Clark became the first Americans to formally record their observations of the landscape and local Indians. These descriptions drew the interest of the United States government, which led to the creation of a fort and the first American settlers in the area.

In the prior year, the United States Congress approved the Louisiana Purchase, which transferred the entire western Mississippi River valley to the U.S. from France.

The treaty more than doubled the land area of the United States and included territory that stretched from New Orleans to present-day Montana, but Europeans and Americans knew virtually nothing about the area. President Thomas Jefferson wanted to ascertain what trading and farming opportunities awaited, make scientific discoveries such as the possibility that mastodons still lived in the remote lands, and perhaps find the elusive "northwest passage," or water route, to the Pacific Ocean. With the approval of Congress, he therefore commissioned the "Corps of Discovery" to journey to the continent's west coast, beyond even the land that America had purchased, and bring back detailed surveys and journals.

Leading the 43-person expedition were Jefferson's personal aide and friend, Meriwether Lewis, and a former army officer named William Clark. Assisting the expedition was a man named York, a slave owned by Clark and the first recorded visitor of African descent to many of the areas visited by the explorers. In May 1804, Lewis and Clark departed from St. Louis (a French-founded outpost on what was then the western edge of the United States) and traveled upstream along the Missouri River on an oar and sail-powered keelboat as well as two smaller boats and a group marching on the banks with two horses.

When Lewis and Clark reached the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas (or "Kaw") Rivers on June 26, 1804, they began making some of the first observations about the site of Kansas City that still survive today. Clark's journal recorded the first sight of the Kansas River, writing in his journal, "we rowed round it [a sandbar] and came to & camped, in the Point above the Kansas River." Lewis and Clark set up camp above the mouth of the Kansas River, in present-day Kansas City, Kansas, and remained for three days to rest and repair their boats.

In 1744, French fur traders had constructed an outpost, known as Fort Cavagnial, near present-day Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to trade with the Osage and Kansa Indians, but little reliable information about the area had endured. The Corps of Discovery thereby made the earliest surviving observations about the Kansas City area. They noted that the Kaw River water was dirty and unsuitable for drinking. Imposing limestone bluffs overlooked the rivers, but they made no mention of the possibility that a large city might one day occupy the land.

The condition of the travelers was a more pressing concern. Just 250 miles into what became an 8,000 mile trip, some of the travelers already suffered from dysentery and boils. Discipline broke down when John Collins, a drunken soldier who was supposed to guard the supplies, slept while another member of the expedition, Hugh Hall, stole all of the whiskey. Hall was punished with 50 lashes and Collins with 100. Equally disconcerting was the possibility that the nearby Kansa Indians would not welcome their presence. Clark commented about them in his journal; "I am told they are a fierce & warlike people, being badly Supplied with fire arms."

Despite only spending a few days in the area, and a couple more on the return journey in 1806, Lewis and Clark left a lasting impact on its future development. The journals of Lewis and Clark sparked interest in the West, especially for its beaver pelts and Indian traders who were mostly friendly to the expedition. The grasslands of the Great Plains did not seem to offer resources for large cities, but Lewis and Clark's observations caught the attention of the French fur-trading family headed by half-brothers Auguste and Jean Pierre Chouteau. Jean Pierre's son, Francois Chouteau, went on to establish the first permanent white settlement in present-day Kansas City in 1821.

A more immediate effect resulted from William Clark's remark in his journal that a limestone bluff 25 miles east of present-day Kansas City offered a perfect location for a fort and trading post. The treaty that allowed the establishment of a fort at that location required the Osage Indians to cede 52.5 million acres of land in the territories of Missouri and northern Arkansas to the United States. With great difficulty, the U.S. Army completed Fort Osage on November 10, 1808, within the boundaries of what is now Jackson County. It served as an official trading and military outpost of the U.S. Government until 1822, when private companies took control of the fur trade nationwide.

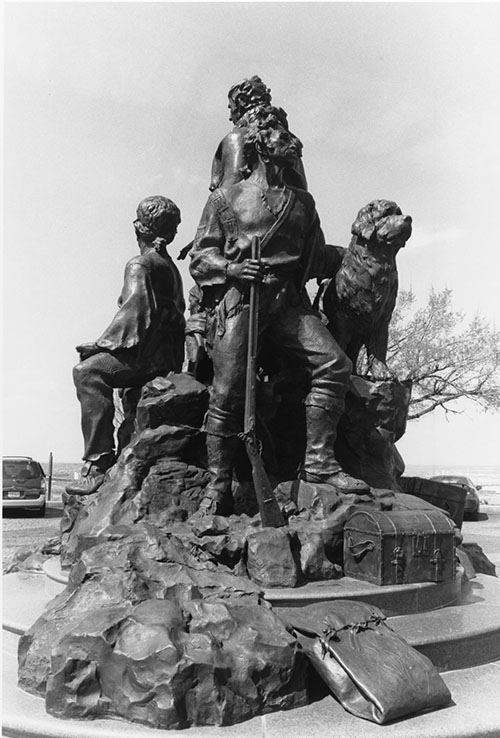

The results of Lewis and Clark's expedition for Kansas City were two-fold. On the one hand, their surveys and observations led to the first permanent American settlements in the area. These settlers eventually displaced the Osage Indians from western Missouri and then present-day downtown Kansas City in 1825. The Osage were forced to relocate to a reservation in Kansas that year, and then had to move again to Oklahoma in the 1870s. The settlers who moved to what is now Jackson County, Missouri built the towns and cities of Independence, Westport, and Kansas City that became an important part of the American West in the mid-19th century. Lewis and Clark's three-day stay at the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas Rivers was humble enough, but it did signal the great changes that would come over the next half-century. Today a statue honoring the expedition resides in Case Park, at 8th and Jefferson streets in Kansas City, Missouri.

View images relating to Lewis and Clark that are a part of the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

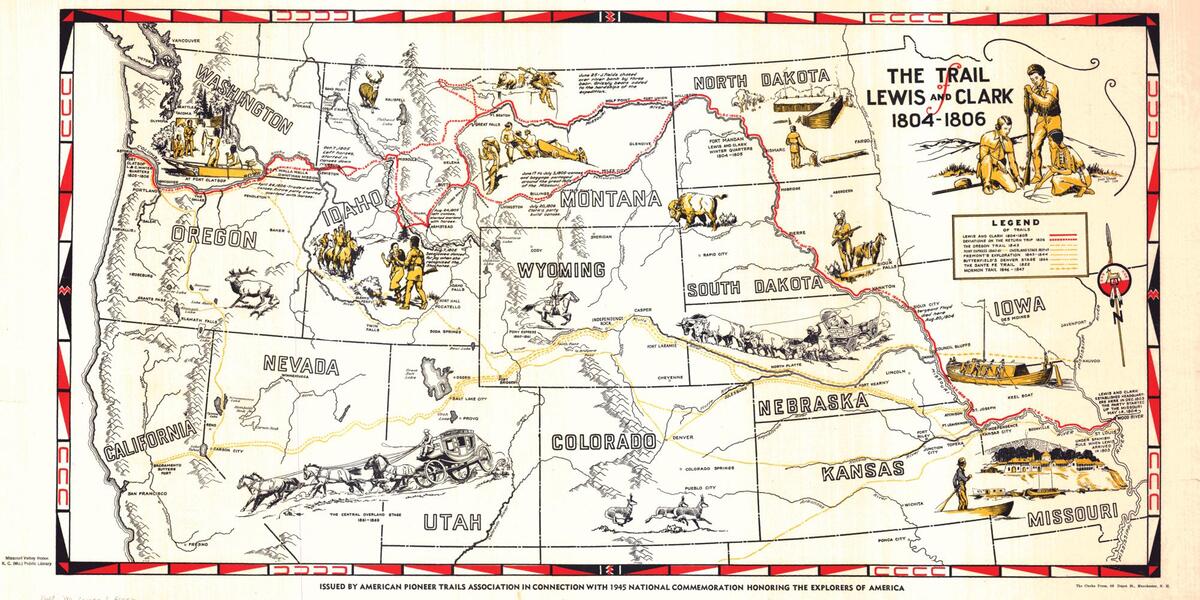

- The Trail of Lewis and Clark 1804-1806; illustrated map, 1945.

- Corps of Discovery Sculpture in Case Park

- Corps of Discovery Sculpture in Case Park; alternative view.

- Postcard of George Fuller Green painting of Fort Osage; located on a strategic site designated by William Clark; accompanied by a brief historical article.

- Postcard of the Factor's House at Fort Osage; accompanied by a brief historical article.

- Postcard of Watts Mill; owned by Anthony Watts, son of a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition; accompanied by a brief historical article.

- Lewis and Clark Point, 1950

Check out the following books, articles, and films about Lewis and Clark, held by the Kansas City Public Library:

- Exploring Lewis & Clark's Missouri, by Brett Dufur and Kerry Mulvania, 2004; 256 pp.

- "Lewis & Clark: The Corps of Discovery in Missouri," (VHS), produced by Kipp Woods, Missouri Department of Conservation, 2001.

- Lewis & Clark in Missouri: Follow Their Footsteps, Follow the Rivers, by the Missouri Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Commission, 2002; 19 pp.

- The Missouri River, by John Hamilton, 2003; Children's book describes Lewis and Clark's journey through Missouri; 32 pp.

- "Lewis and Clark at the Bend of the Missouri River 1804-06: A Spark of Kansas City," by Pete Cuppage, in The Historical Journal of Wyandotte County, Summer 2002.

- "Kaw Point Entries: Historic Lewis and Clark Sites in Wyandotte County," by Loren Taylor, in The Historical Journal of Wyandotte County, June 25, 1905.

- Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States, by Robert B. Roberts; contains a reference to Fort Osage, the first government outpost in the Louisiana Territory.

- Search the Kansas City Public Library catalog for hundreds of additional entries about Lewis and Clark's Corps of Discovery.

Continue researching Lewis and Clark using archival materials from the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-1806; republished.

- Lewis and Clark Print, 2002

- Vertical File: Lewis and Clark Bicentennial

- 1807 Patrick Gass Journal; Glass was a sergeant with the Lewis and Clark expedition, original copy.

References:

Rick Montgomery & Shirl Kasper, Kansas City: An American Story (Kansas City, MO: Kansas City Star Books, 1999), 6, 14, 85.

Sherry Lamb Schirmer and Richard D. McKinzie, At the River’s Bend: An Illustrated History of Kansas City (Woodland Hills, CA: Windsor Publications, 1982), 11-13.

Roy Ellis, A Civic History of Kansas City, Missouri (Springfield, MO: Press of Elkins-Swyers Co., 1930), 1.

Charles E. Coulter, Take Up the Black Man’s Burden: Kansas City’s African American Communities, 1865-1939 (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2006), 19.

Dory DeAngelo, What About Kansas City!: A Historical Handbook (Kansas City, MO: Two Lane Press, 1995), 14-17.

Shirley Christian, Before Lewis and Clark: The Story of the Chouteaus, the French Dynasty that Ruled America's Frontier (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004), 8-9, 28-29.