December 31, 1900: With the temperature hovering near zero degrees, some 15,000 people gathered in Kansas City's Convention Hall to welcome the beginning of the 20th century. The revelers were in an optimistic, even jubilant mood. In just 50 years, the region that is now greater Kansas City had grown from a few small towns into a thriving metropolitan area of 268,000. While Kansas City's high poverty levels and poor public sanitation remained serious problems, (even by the standards of 1900) the future looked bright. For the United States as a whole, the 20th century seemed likely to witness great improvements in civic institutions and continuing technological achievements.

This Week in Kansas City History

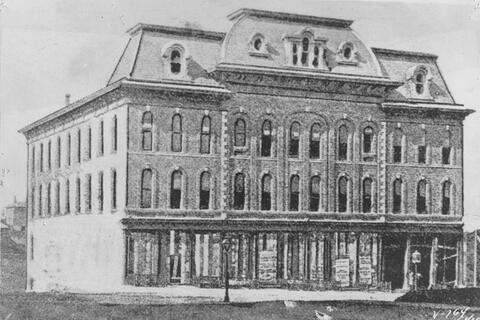

January 31, 1901: The Coates Opera House, which was Kansas City’s original first-class theater, met a fate common among nineteenth-century theaters when it burned to the ground. Boiler rooms for heating, hot gas or electric stage lights, and large crowds of people crammed into small spaces made theatergoing a distinct fire hazard. The 31-year-old building burned to the ground shortly following the performance of Heart and Sword, starring Walker Whiteside and Leilia Wolstan. Had the two actors performed the longer Hamlet, as originally scheduled, hundreds of occupants would have been in danger. Fortunately, no one was harmed in the disaster as the actors who remained in the building broke through windows to escape.

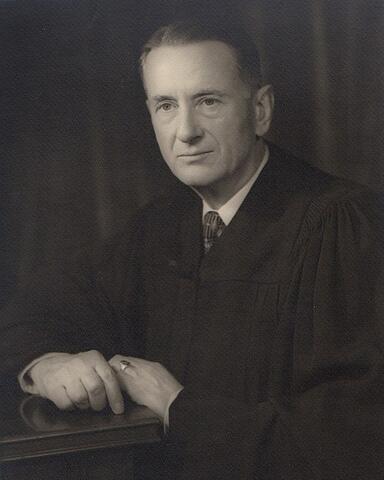

February 22, 1901: Future Supreme Court justice Charles Evans Whittaker was born near Troy, Kansas. As a young adult, he moved to Kansas City, where he earned a degree from the Kansas City School of Law and then went on to practice law for 30 years. In a space of just three years, starting in 1954, he transitioned into the U.S. District Court of the Western District of Missouri, the Eighth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, and finally to serve as a Supreme Court associate justice.

August 5, 1901: In 1887, a new main pavilion for Kansas City's annual industrial exposition opened to throngs of visitors, including President Grover Cleveland. Dubbed "the Crystal Palace" the building enclosed more than 740,000 square feet of exposition space and contained a remarkable 80,000 square feet of glass roofing. When completed, it was among the grandest structures in the mid-western United States. Just 14 years later, though, the Crystal Palace lay abandoned, awaiting demolition. In a suspected but unproven case of arson, the building burned to the ground before it could be demolished.

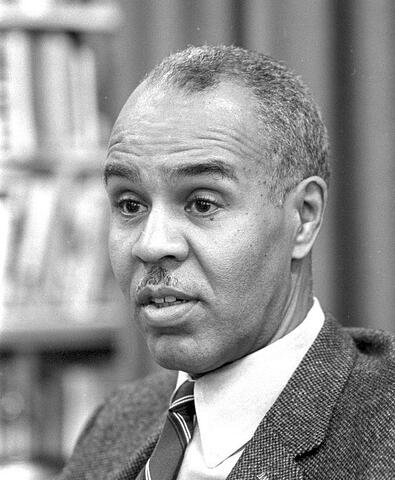

August 30, 1901: Roy O. Wilkins was born in St. Louis, Missouri. From a modest background, Wilkins would go on to graduate from the University of Minnesota, become the editor of the Kansas City Call newspaper, and lead the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for more than two decades at the height of the civil rights movement. Despite possessing college degrees, Roy Wilkins's parents struggled to make ends meet. They had moved to St. Louis so that Roy's father, William Wilkins, could find work.

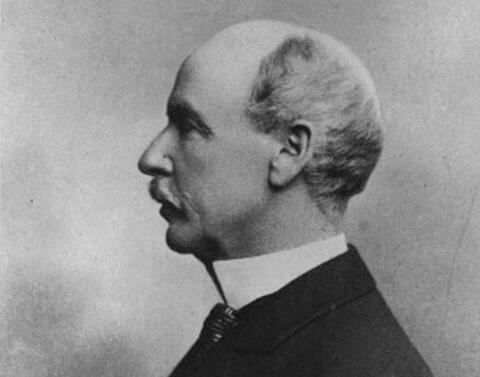

December 2, 1905: Kansas City lost its lead proponent of the park and boulevard movement with the death of August Meyer. Meyer was born in St. Louis in 1851 to German immigrant parents. As a young adult, he studied engineering in Europe and then entered the mining business in Leadville, Colorado, where he grew wealthy. When he moved to the Kansas City area in 1881, he purchased the Consolidated Kansas City Smelting and Refining Company in Argentine, Kansas.

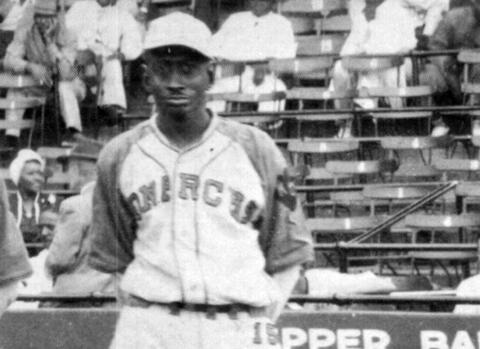

July 7, 1906: Leroy "Satchel" Paige, one of baseball's finest pitchers, was most likely born on July 7, 1906. While Paige believed this date to be correct, poorly kept records left his exact birth year and date unclear. By contrast, there is no doubt that he was one of the greatest pitchers of all time. His long career included a critical stint with the Kansas City Monarchs Negro leagues baseball team between 1939 and 1947, during which he recovered from an injury to re-launch his career.

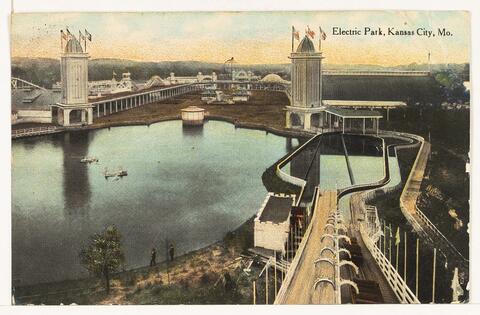

May 19, 1907: 53,000 people attended the opening day of the new Electric Park. Originally conceived as a ploy to bring customers to visit the Heim Brewing Company in 1899, the park had grown into an attraction in its own right. Each night, the 100,000 lights that gave the park its name illuminated a roller coaster, scenic railway, carousel, skating rink, swimming pool, bowling alley, alligator farm, dime museum, theaters, dance pavilions, bandstand, penny arcade, shooting gallery, flower beds, a lake, and rental boats. Most alluring were the nightly performances of costumed young women who danced to a colorful electric light show on a platform on a large fountain in the center of the lake. The park, sometimes known as Kansas City's Coney Island, continued to serve the city's greatest amusement park for nearly two decades.

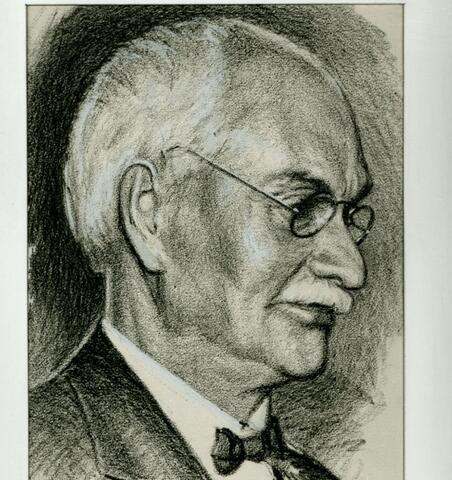

April 14, 1910: The City Council approved the creation of the Board of Public Welfare to provide aid to the city’s poor. As the brainchild of Kansas City philanthropist William Volker, the Board of Public Welfare was the first modern welfare department in the United States and a groundbreaking forerunner to modern welfare programs. The board was just one of Volker’s many memorable contributions that included the creation of Research Hospital, the establishment of the University of Kansas City (now UMKC), the purchase of the land for Liberty Memorial, and thousands of individuals who received some of his money when in need.

May 16, 1910: In one of the most notorious trials in Kansas City's history, a jury found Doctor Bennett Clark Hyde guilty of murdering Kansas City real estate developer and philanthropist "Colonel" Thomas H. Swope. Despite strong evidence linking Hyde to the crime, this verdict would be overturned by a higher court in a few months time, leaving the city to ponder whether Hyde had committed the murder.